Why “China Plus One” Has Become “Anywhere but China”

In an era of simmering tensions with China and an increasingly incendiary trade war, the merits of the China Plus One sourcing strategy are growing by the week.

This article is part one of a two-part series exploring how the China Plus One sourcing trend has evolved during the 2020s, and how recent geopolitical developments have turned it into a strategic imperative.

At some point in the middle of the 2010s, many large multinational companies started rethinking their sourcing strategies. A significant number of these firms were reliant on China for large swaths of their manufacturing operations, depending on the so-called “world’s factory” because of the country’s modest labor costs, immense production capacity, and vast workforce. While this sourcing practice dated back several decades—to the early chapters of globalization in the 1980s and 1990s, at least—it was no longer quite as advantageous as it had once been.

Why China Began to Fall Out of Favor with Businesses

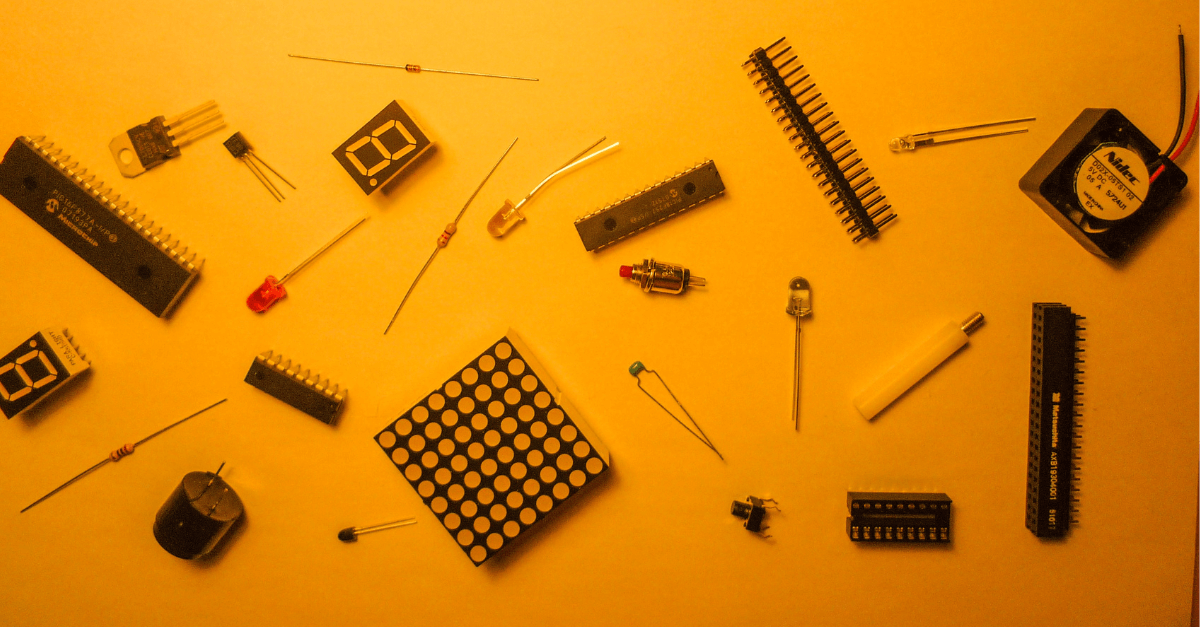

By the mid-2010s, China was emerging as one of the world’s largest economies, an unparalleled manufacturing hub that dominated in industries ranging from electronics to textiles. As a result of their growing entrenchment in these global sectors—along with an emerging middle class and the increased affluence that comes with it—the cost of doing business in China was ticking up. Labor was no longer as cheap as it had been during the latter decades of the 20th century, and local manufacturers were having to charge their global customers higher prices for parts, subassemblies, and other products. These higher costs were pushing American and European businesses to start venturing elsewhere for new, cheaper manufacturing prospects. As UCLA supply chain management expert Christopher Tang told StrategicRISK last year, “Rising labor costs in China…prompted Western firms to consider a ‘China Plus One’ strategy by establishing production facilities in Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia.”

Fast-forward to the 2020s, and China Plus One has evolved even further, moving beyond a niche alternative sourcing strategy to a critical, omnipresent feature of global procurement. How did China’s manufacturing dominance—and persistent presence in so many industry supply chains—shift so quickly?

How the Pandemic Turbocharged the “China Plus One” Strategy

As it has done with many aspects of society, the COVID-19 pandemic played a pivotal role in accelerating China Plus One. At the height of the pandemic, in 2020 and 2021, the virus was unleashing a wide range of supply chain crises, including supply shortages, shipping container snarls at major international ports, and factory shutdowns. In the years since, economists and public policy researchers have estimated that the U.S. revenue loss attributable to the pandemic could eventually rise to as much as $14 trillion. And while only a fraction of that staggering figure stems from supply chain disruptions, even a small percentage represents tens of billions of dollars.

During that turbulent era, many multinational firms realized just how dependent their businesses were on Chinese manufacturing. China’s Zero-COVID policy—which implemented lockdowns, quarantines, and rigorous contact tracing to minimize the impact of the virus in the country—triggered shortages for a slew of global corporations, including Apple and various Western automakers. Whether from restrictions imposed on large manufacturing hubs, logistics slowdowns, or new variants generating outbreaks that lasted months, companies in the U.S. and Europe were getting throttled by pandemic disruptions in China. In short, COVID-19 laid bare one specific aspect of the unique interdependence created by highly globalized supply chains: bottlenecks that started in China rarely stayed in China. Instead, they reverberated all over the globe.

In short, COVID-19 laid bare one specific aspect of the unique interdependence created by highly globalized supply chains: bottlenecks that started in China rarely stayed in China.

In the aftermath of those years, many corporations with large manufacturing operations began joining in what would become a consistent refrain: “never again.” U.S. businesses were determined to not leave themselves so vulnerable in the future, with disproportionate dependence on China and a lack of viable alternatives that could be called upon when disaster struck. Rather than relying heavily on Chinese manufacturing for products and parts, firms vowed to start diversifying their supply chains, seeking out other countries and manufacturing centers that could help them become more agile, cultivate greater supply chain resilience, and even lower costs.

Recent statistical evidence shows that the U.S. has shifted away from Chinese manufacturing in fairly dramatic fashion over the past half-decade. According to research published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in 2024, “The United States has decreased its dependence on China for all types of imported manufactured goods since 2018.” Customs data shows that the U.S. has shifted supply chains away from China and toward trade partners like Mexico, Canada, the E.U., and Vietnam. Following decades of China maintaining or increasing its exports to the U.S., recent years have seen a stark and telling reversal of that trend.

While data is not yet available through 2024, there’s plenty of reason to think that U.S. supply chains continued shifting away from China, restructuring sourcing around American allies and Chinese competitors.

The ASEAN Bloc and the China Challengers

Over the first half of the 2020s, a cluster of nations in Southeast Asia has emerged as willing and capable alternatives to Chinese manufacturing. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations—known as ASEAN—is comprised of ten countries in Southeast Asia:

- Indonesia

- Vietnam

- Thailand

- Malaysia

- Philippines

- Singapore

- Cambodia

- Myanmar

- Laos

- Brunei

Over the past five years, these 10 nations have played an outsized role in the global supply chain diversification away from China. Countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand are expanding their manufacturing capacities and expertise in industries ranging from automotive and electronics to semiconductors and electric vehicle (EV) batteries, enhancing their competitiveness and viability to step into the gap that China Plus One has pried open. To cite just one example, Malaysia has spent years fostering its back-end semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem, and is now responsible for 13% of the entire global market for semiconductor assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP).

To cite just one example, Malaysia has spent years fostering its back-end semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem, and is now responsible for 13% of the entire global market for semiconductor assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP).

Recent insights from analysts at S&P Global sum up this transition well. “Foreign direct investment (FDI) data and anecdotal evidence show Southeast Asia’s increasing importance as a China Plus One destination for mainland Chinese and foreign companies,” the analysts wrote. “Notable examples include investments to build a chip-testing and packaging factory in Malaysia, a mines-to-manufacturing electric vehicle supply chain in Indonesia, and an expansion of consumer electronics production facilities in Vietnam.”

The “Shoring” Wave: Mexico, Canada, Vietnam & More

In addition to the ascendance of these ASEAN nations, another trend has emerged under the larger China Plus One strategic shift. Following the disruptions and volatility of the COVID-19 pandemic, some businesses started reconsidering the merits of complex supply chains rooted halfway across the world. Instead of depending on factories and facilities for which they had minimal visibility or oversight, they began entertaining the potential virtues of shifting sourcing and procurement to closer geographical regions. This thinking has given rise to the phenomena of onshoring, nearshoring, and friendshoring, three distinct but interrelated ways to reduce risk, increase visibility, and gain better control over supply chains.

Some supply chain veterans might assume that these trends are just industry buzzwords, talking points that aren’t actually borne out by real sourcing decisions and habits. The data, however, vigorously support the shift. According to research conducted by the The Reshoring Initiative, a nonprofit focused on helping U.S. businesses move manufacturing jobs back to America, in 2022 there were a total of 360,000 jobs that were either reshored to the U.S. or created as a result of foreign direct investment. This represented an increase of over 50% from the prior year. And while 2023 experienced a slight slowdown in this collective onshoring effort, the NGO still reported close to 300,000 jobs either reshored or produced in the U.S. via FDI.

In terms of nearshoring and friendshoring, recent patterns demonstrate that America is strengthening its trade with nations like Mexico, Canada, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Imports from the latter country, in fact, doubled between 2017 and 2022, according to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, as Vietnam asserted itself as a reliable, cost-effective alternative to Chinese manufacturing.

It’s true that some of these relationships are now being strained, if not outright jeopardized, by current U.S. trade policy. The larger evolution of supply chains, however, is a multi-year trend that transcends presidential administrations. Even as short-term dynamics complicate specific trade relationships, this trajectory will continue to favor countries that are either geographically proximate to the U.S. or have friendly diplomatic relations with America.

How the Trade Wars Raised the Stakes for Manufacturers

The ongoing trade conflict between the U.S. and China over the past few years has further accelerated the China Plus One sourcing strategy. Beginning with technology restrictions imposed by the U.S. Commerce Department in 2020, these trade wars have come to engulf a slew of the largest and most critical industries in the world, including electronics, semiconductors, and rare earth minerals. While President Biden took a more gradual, methodical approach to trade barriers than Trump’s first administration, his agencies still imposed stiff, sweeping bans on leading-edge technology and hardware being exported to China. Beijing and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) responded with their own limits on critical mineral exports like gallium and germanium.

Between 2021 and 2024, the U.S. imposed a battery of restrictions intended to hamper China’s technological advancement while ensuring that the U.S. maintains a healthy—even insurmountable—lead in cutting-edge semiconductor technology.

U.S.-China Trade War Timeline

- October 2022: the Bureau of Industry and Security implemented sweeping semiconductor export controls on China. Among other restrictions, BIS added a number of specific semiconductors and related hardware to its Commerce Control List (CCL); introduced new Foreign Direct Product Rules (FDPRs) that curbed hardware manufactured using U.S. technology from being sold to China; and added over 30 companies to the Entity List.

- May 2023: Although China has not always responded in kind to the U.S.’s trade actions, the PRC has carried out measured responses intended to hamstring U.S. industry. In May 2023, the government banned U.S.-based semiconductor manufacturer Micron from major infrastructure projects in China. The Cyberspace Administration of China said that Micron’s products pose “serious network security risks, which pose significant security risks to China's critical information infrastructure supply chain, affecting China's national security."

- October 2023: In 2023, the Biden administration made targeted changes to the trade barriers imposed a year earlier. These revisions, which sought to block loopholes and broaden the scope of restrictions, consisted of three main amendments. BIS expanded the types of semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) that was subject to its export controls; tweaked the parameters for what types of chips fell within the scope of restrictions; and added 13 more Chinese businesses to the Entity List—firms that the federal government asserts are involved in developing artificial intelligence with military applications.

- December 2024: In response to a succession of trade actions against China over the previous two years, the PRC banned exports of gallium, germanium, antimony, and several other key minerals to the U.S. As the Chinese Commerce Ministry explained, “In principle, the export of gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard materials to the United States shall not be permitted.” Gallium and germanium are key materials in semiconductor manufacturing. In 2024, China accounted for over 98% of the global output of refined gallium, and nearly 60% of refined germanium.

The geopolitical tension and retaliatory trade restrictions between the U.S. and China have increased the risks associated with sourcing from China in several ways.

The geopolitical tension and retaliatory trade restrictions between the U.S. and China have increased the risks associated with sourcing from China in several ways.

- First, importing goods from China is getting more expensive. Over the past six weeks alone, the Trump administration has twice implemented 10% tariffs on all Chinese goods—duty rates that have been imposed over and above preexisting tariffs inherited from the Biden administration.

- Second, as this trade conflict intensifies, there’s a growing chance that China will eventually impose its own export controls on semiconductors, electronics, and other related goods. They’ve already implemented controls for critical minerals, including gallium and germanium. While these types of restrictions would almost certainly negatively impact a Chinese economy that exports huge quantities of chips and other hi-tech commodities, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) may eventually feel they have little choice. After years of absorbing blows from the U.S. government aimed at hampering the nation’s technological advancement, the CCP could eventually decide to strike American industry where it will inflict the most possible damage.

- Third, Chinese manufacturers are at heightened risk of being sanctioned by the U.S. government. The U.S. Department of Commerce currently has over 700 Chinese firms on sanctions lists, and over the past 13 months alone the UFLPA has added 100 firms to its Entity List. American businesses sourcing from a supplier that becomes sanctioned could face sudden shortages or be cut off from critical parts completely, threatening production and manufacturing continuity.

These are just a few scenarios that demonstrate how the ongoing chip wars and larger trade conflict between the U.S. and China are changing the composition and stakes of China Plus One. Given the evolving conditions in 2025, there is now a strong imperative for Western companies to either embrace China Plus One or else abandon China completely—a “Plus Many” strategy that is rapidly gaining traction in global manufacturing.

Part two of this deep-dive into the current state of China Plus One will be published Tuesday, March 18.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Z2Data Solution

Z2Data is a leading supply chain risk management platform that helps organizations identify supply chain risks, build operational resilience, and preserve product continuity.

Powered by a proprietary database of 1B+ components, 1M+ suppliers, and 200K manufacturing sites worldwide, Z2Data delivers real-time, multi-tier visibility into obsolescence/EOL, ESG & trade compliance, geopolitics, and supplier health. It does this by combining human expertise with AI and machine learning capabilities to provide trusted insights teams can act on to tackle threats at every stage of the product lifecycle.

With Z2Data, organizations gain the knowledge they need to act decisively and navigate supply chain challenges with confidence.

.svg)